|

| University of Illinois' fictional mascot Chief Illiniwek was banned by the NCAA in 2007. |

A new chapter was written last Thursday in their crusade.

Six American Indian students at the University of North Dakota filed a federal lawsuit to eliminate the school's "Fighting Sioux" nickname. According to a report on CBSSports.com:

"The Legislature earlier this year passed a bill requiring UND to keep the nickname and logo even though the school had begun efforts to retire it. The NCAA said UND will face sanctions if it remains. The school will be barred from hosting NCAA postseason games and its teams will not be able to wear the nickname and logo on its uniforms in postseason contests.The controversy began in 2006, when the NCAA placed the UND "Fighting Sioux" on the list of schools with "hostile and abusive" mascots and nicknames. Of the two namesake tribes in the state, the Spirit Lake Sioux members voted, in a referendum, to support the nickname, while the Standing Rock Sioux refused to change its oppositional stance. The NCAA asked UND to retire the nickname as of August 15, assuming that it did not receive unanimous tribal approval.

The students bringing the lawsuit are Amber Annis, Lisa Casarez, William Crawford, Sierra Davis, Robert Rainbow, Margaret Scott, Franklin Sage and Janie Schroeder. In addition to their complaints about the state law and settlement agreement, the suit alleges that the nickname has had 'a profoundly negative impact' on their self-image and psychological health, and has deprived them 'of an equal educational experience and environment.'"

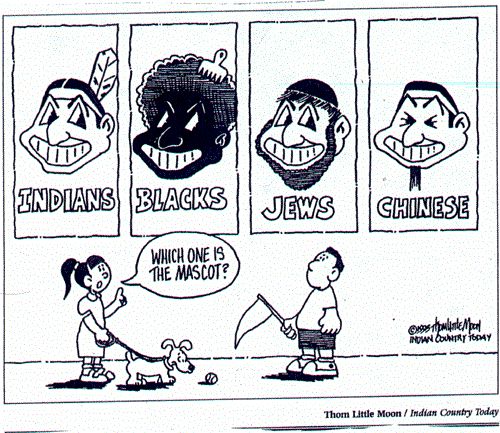

Activists began fighting against discriminatory mascots and nicknames in the 1960s, but their efforts didn't bear fruit until the 1990s. In the last few decades, scores of schools from the elementary to college levels have changed their mascots out of respect for American Indian culture. Just to name a few: Marquette Warriors became Marquette Golden Eagles, St. John's Redmen became St. John's Red Storm, and Seattle University Chieftains became the Redhawks.

Other schools have reached out to make connections with the tribes associated with their nicknames and mascots. The Florida State Seminoles are a prominent example. FSU has had a long history of problematic mascots, but in 1972, they retired "Sammy Seminole" and "Chief Fullabull" in favor of Chief Osceola, whose actions and appearance were carefully designed with the help of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. The school maintains a working relationship with the tribe to this day, which led to a recent NCAA exception from the "hostile and abusive" list. Other schools have followed suit. The University of Utah has received permission to use the nickname "Utes" from the Ute Tribe. The Central Michigan University Chippewas have the endorsement of Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Nation of Michigan.

But, as evidenced by UND's staunch defense of its nickname and mascot, those who haven't changed have dug in and thrown up a weak wall of hollow arguments to deflect criticism.

One of the many questionable points American Indian mascot supporters make is that the nicknames themselves aren't offensive because they represent something from the past. In an editorial in the Boston Globe from June 5, 2005:

The use of Aztec or Seminole as a nickname by itself would not appear to be racist, as such names refer to a particular civilization rather than an entire race of people. In this way, they are no different from other school nicknames such as Trojans and Spartans (like Aztecs, ancient peoples) or Fighting Irish and Flying Dutchmen (like Seminoles, nationalities). Similarly, Warriors and Braves are no different from the fighting men of other cultures, like Vikings, Minutemen, or Musketeers (all current NCAA mascots, the first of which is also an NFL mascot) so it seems hard to argue that their use is uniquely demeaning in some way.This argument is overly simplistic. The cultures that embraced the Trojan, Spartan, Viking, and even Aztec warriors are far removed from the present. The Indian Brave and the Indian Warrior are an integral part of the culture of many peoples that have a long, brutal, and sad history in relation to the founding and development of the United States. The continued use of the Brave and the Warrior (and others) as mascots for American sports teams is, in itself, an extension of colonialism. We have your land, we murder your people, we own your traditions.

|

| In or out of perspective, Chief Wahoo is an offensive caricature. |

"[The name Redskin] symbolizes courage, dignity, and leadership...Redskins symbolize the greatness and strength of a grand people."Many of the most contentious mascots, usually in professional sports, like the Washington Redskins, Kansas City Chiefs, Atlanta Braves, Cleveland Indians, and Chicago Blackhawks have been deemed acceptable by the teams themselves and their fans.

If any one thing bothers American Indian activists, it's this. In that same Sports Illustrated article, Michael Yellow Bird, associate professor of social work at Arizona State, blasts this type of thinking:

"This is no honor...We lost our land, we lost our languages, we lost our children. Proportionately speaking, indigenous peoples [in the U.S.] are incarcerated more than any other group, we have more racial violence perpetrated upon us, and we are forgotten. If people think this is how to honor us, then colonization has really taken hold."In addition, many sports teams butcher historical fact in their portrayal of Native peoples and understanding of their cultures. They wear contradictory clothing, confuse basic traditions, and generally refuse to educate themselves.

That said, college, high school, middle school, and elementary schools are all making positive strives to eliminate ignorance and promote understanding of American Indian culture. University of North Dakota will eventually have to change mascots, thanks to the efforts of the NCAA.

Yet, professional franchises, with the lack of a powerful governing body, can get away with shooing away activists or ignoring them altogether. They fear a name change will have adverse financial consequences.

But when one of the biggest teams in sports still operates with a racial slur in its name (Washington), when logos with names like Chief Wahoo are still widely publicized on merchandise (Cleveland), when fans don face paint and do the tomahawk chop (Atlanta), and when the phrase "kill the Indians" can be uttered without any reprimand, we know we, America, have an unresolved issue on our hands.

Hate the column? Love the column? Send us an email at jabronifreesports@gmail.com.

Dean Karoliszyn is the Editor-in-Chief and cofounder of Jabroni Free Sports.

No comments:

Post a Comment